A flow on a graph ![]() is an assignment to each edge of

is an assignment to each edge of ![]() of a direction and a non-negative integer (the flow in that edge) such that the flows into and out of each vertex agree. A flow is nowhere zero if every edge is carrying a positive flow and (confusingly) it is a

of a direction and a non-negative integer (the flow in that edge) such that the flows into and out of each vertex agree. A flow is nowhere zero if every edge is carrying a positive flow and (confusingly) it is a ![]() -flow if the flows on each edge are all less than

-flow if the flows on each edge are all less than ![]() . Tutte conjectured that every bridgeless graph has a nowhere zero

. Tutte conjectured that every bridgeless graph has a nowhere zero ![]() -flow (so the possible flow values are

-flow (so the possible flow values are ![]() ). This is supposed to be a generalisation of the

). This is supposed to be a generalisation of the ![]() -colour theorem. Given a plane graph

-colour theorem. Given a plane graph ![]() and a proper colouring of its faces by

and a proper colouring of its faces by ![]() , push flows of value

, push flows of value ![]() anticlockwise around each face of

anticlockwise around each face of ![]() . Adding the flows in the obvious way gives a flow on

. Adding the flows in the obvious way gives a flow on ![]() in which each edge has a total flow of

in which each edge has a total flow of ![]() in some direction.

in some direction.

Seymour proved that every bridgeless graph has a nowhere zero ![]() -flow. Thomas Bloom and I worked this out at the blackboard, and I want to record the ideas here. First, a folklore observation that a minimal counterexample

-flow. Thomas Bloom and I worked this out at the blackboard, and I want to record the ideas here. First, a folklore observation that a minimal counterexample ![]() must be cubic and

must be cubic and ![]() -connected. We will temporarily allow graphs to have loops and multiple edges.

-connected. We will temporarily allow graphs to have loops and multiple edges.

We first show that ![]() is

is ![]() -edge-connected. It is certainly

-edge-connected. It is certainly ![]() -edge-connected, else there is a bridge. (If

-edge-connected, else there is a bridge. (If ![]() is not even connected then look at a component.) If it were only

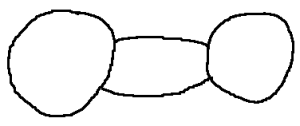

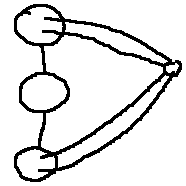

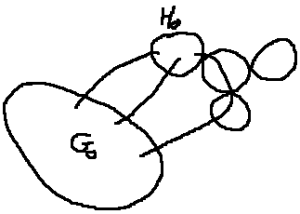

is not even connected then look at a component.) If it were only ![]() -edge-connected then the graph would look like this.

-edge-connected then the graph would look like this.

Contract the top cross edge.

If the new graph has a nowhere zero ![]() -flow then so will the old one, as the flow in the bottom cross edge tells us how much flow is passing between the left and right blobs at the identified vertices and so the flow the we must put on the edge we contracted. So

-flow then so will the old one, as the flow in the bottom cross edge tells us how much flow is passing between the left and right blobs at the identified vertices and so the flow the we must put on the edge we contracted. So ![]() is

is ![]() -edge connected.

-edge connected.

Next we show that ![]() is

is ![]() -regular. A vertex of degree

-regular. A vertex of degree ![]() forces a bridge; a vertex of degree

forces a bridge; a vertex of degree ![]() forces the incident edges to have equal flows, so the two edges can be regarded as one. So suppose there is a vertex

forces the incident edges to have equal flows, so the two edges can be regarded as one. So suppose there is a vertex ![]() of degree at least

of degree at least ![]() .

.

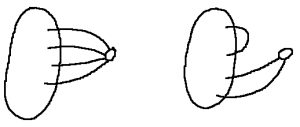

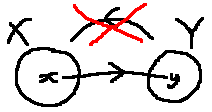

We want to replace two edges ![]() and

and ![]() by a single edge

by a single edge ![]() to obtain a smaller graph that is no easier to find a flow for. The problem is that in doing so we might produce a bridge.

to obtain a smaller graph that is no easier to find a flow for. The problem is that in doing so we might produce a bridge.

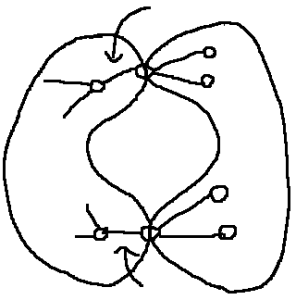

The ![]() -edge-connected components of

-edge-connected components of ![]() are connected by single edges in a forest-like fashion. If any of the leaves of this forest contains only one neighbour of

are connected by single edges in a forest-like fashion. If any of the leaves of this forest contains only one neighbour of ![]() then there is a

then there is a ![]() -edge-cut, so each leaf contains at least two neighbours of

-edge-cut, so each leaf contains at least two neighbours of ![]() .

.

If there is a component of the forest with two leaves then choose ![]() and

and ![]() to be neighbours of

to be neighbours of ![]() from different leaves of that component.

from different leaves of that component.

Otherwise the ![]() -edge-connected components of

-edge-connected components of ![]() are disconnected from each other. Now any such component

are disconnected from each other. Now any such component ![]() must contain at least

must contain at least ![]() neighbours of

neighbours of ![]() , else there is a

, else there is a ![]() -edge-cut. If some

-edge-cut. If some ![]() contains

contains ![]() neighbours of

neighbours of ![]() then we can choose

then we can choose ![]() and

and ![]() to be any two of them. Otherwise all such

to be any two of them. Otherwise all such ![]() contain exactly

contain exactly ![]() neighbours of

neighbours of ![]() , in which case there must be at least two of them and we can choose

, in which case there must be at least two of them and we can choose ![]() and

and ![]() to be neighbours of

to be neighbours of ![]() in different components.

in different components.

So ![]() is

is ![]() -regular and

-regular and ![]() -edge-connected. If

-edge-connected. If ![]() is only

is only ![]() -connected then there is no flow between

-connected then there is no flow between ![]() -connected components, so one of the components is a smaller graph with no nowhere zero

-connected components, so one of the components is a smaller graph with no nowhere zero ![]() -flow. If

-flow. If ![]() is only

is only ![]() -connected then because

-connected then because ![]() is so small we can also find a

is so small we can also find a ![]() -edge-cut.

-edge-cut.

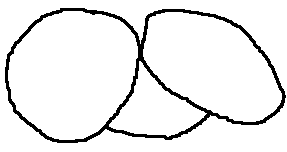

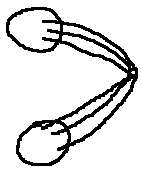

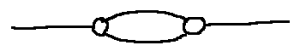

Finally, we want to get rid of any loops and multiple edges we might have introduced. But loops make literally no interesting contribution to flows and double edges all look like

and the total flow on the pair just has to agree with the edges on either side.

We’ll also need one piece of magic (see postscript).

Theorem. (Tutte) Given any integer flow of ![]() there is a

there is a ![]() -flow of

-flow of ![]() that agrees with the original flow mod

that agrees with the original flow mod ![]() . (By definition, flows of

. (By definition, flows of ![]() in one direction and

in one direction and ![]() in the other direction agree mod

in the other direction agree mod ![]() .)

.)

So we only need to worry about keeping things non-zero mod ![]() .

.

The engine of Seymour’s proof is the following observation.

Claim. Suppose that ![]() where each

where each ![]() is a cycle and the number of new edges when we add

is a cycle and the number of new edges when we add ![]() to

to ![]() is at most

is at most ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() has a

has a ![]() -flow which is non-zero outside

-flow which is non-zero outside ![]() .

.

Write ![]() for the set of edges added at the

for the set of edges added at the ![]() th stage. We assign flows to

th stage. We assign flows to ![]() in that order. Assign a flow of

in that order. Assign a flow of ![]() in an arbitrary direction to

in an arbitrary direction to ![]() ; now the edges in

; now the edges in ![]() have non-zero flow and will never be touched again. At the next stage, the edges in

have non-zero flow and will never be touched again. At the next stage, the edges in ![]() might already have some flow; but since

might already have some flow; but since ![]() there are only two possible values for these flows mod

there are only two possible values for these flows mod ![]() . So there is some choice of flow we can put on

. So there is some choice of flow we can put on ![]() to ensure that the flows on

to ensure that the flows on ![]() are non-zero. Keep going to obtain the desired

are non-zero. Keep going to obtain the desired ![]() -flow, applying Tutte’s result as required to bring values back in range.

-flow, applying Tutte’s result as required to bring values back in range.

Finally, we claim that the ![]() we are considering have the above form with

we are considering have the above form with ![]() being a vertex disjoint union of cycles. Then

being a vertex disjoint union of cycles. Then ![]() trivially has a

trivially has a ![]() -flow, and

-flow, and ![]() times this

times this ![]() -flow plus the

-flow plus the ![]() -flow constructed above is a nowhere-zero

-flow constructed above is a nowhere-zero ![]() -flow on

-flow on ![]() .

.

For ![]() , write

, write ![]() for the largest subgraph of

for the largest subgraph of ![]() that can be obtained as above by adding cycles in turn, using at most two new edges at each stage. Let

that can be obtained as above by adding cycles in turn, using at most two new edges at each stage. Let ![]() be a maximal collection of vertex disjoint cycles in

be a maximal collection of vertex disjoint cycles in ![]() with

with ![]() connected, and let

connected, and let ![]() . We claim that

. We claim that ![]() is empty. If not, then the

is empty. If not, then the ![]() -connected blocks of

-connected blocks of ![]() are connected in a forest-like fashion; let

are connected in a forest-like fashion; let ![]() be one of the leaves.

be one of the leaves.

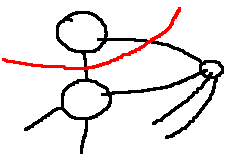

By ![]() -connectedness there are three vertex disjoint paths from

-connectedness there are three vertex disjoint paths from ![]() to

to ![]() . At most one of these paths travels through

. At most one of these paths travels through ![]() ; let

; let ![]() and

and ![]() be endpoints of two paths that do not. These paths must in fact be single edges, as the only other way to get to

be endpoints of two paths that do not. These paths must in fact be single edges, as the only other way to get to ![]() would be to travel through

would be to travel through ![]() . Finally, since

. Finally, since ![]() is

is ![]() -connected it contains a cycle through

-connected it contains a cycle through ![]() and

and ![]() , contradicting the choice of

, contradicting the choice of ![]() .

.

Postscript. It turns out that Tutte’s result is far from magical; in fact its proof is exactly what it should be. Obtain a directed graph ![]() from

from ![]() by forgetting about the magnitude of flow in each edge (if an edge contains zero flow then delete it). We claim that every edge is in a directed cycle.

by forgetting about the magnitude of flow in each edge (if an edge contains zero flow then delete it). We claim that every edge is in a directed cycle.

Indeed, choose a directed edge ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the set of vertices that can be reached by a directed path from

be the set of vertices that can be reached by a directed path from ![]() and let

and let ![]() be the set of vertices that can reach

be the set of vertices that can reach ![]() by following a directed path. If

by following a directed path. If ![]() is not in any directed cycle then

is not in any directed cycle then ![]() and

and ![]() are disjoint and there is no directed path from

are disjoint and there is no directed path from ![]() to

to ![]() . But then there can be no flow in

. But then there can be no flow in ![]() , contradicting the definition of

, contradicting the definition of ![]() .

.

So as long as there are edges with flow value at least ![]() , find a directed cycle containing one of those edges and push a flow of

, find a directed cycle containing one of those edges and push a flow of ![]() through it in the opposite direction. The total flow in edges with flow at least

through it in the opposite direction. The total flow in edges with flow at least ![]() strictly decreases, so we eventually obtain a

strictly decreases, so we eventually obtain a ![]() -flow.

-flow.